Interest rates in India have come full circle in this decade. At the turn of the century, the economy was growing at a lazy 5.5 per cent. Demand for credit was low and interest rates were falling. Then, the Great Indian 8-per cent Growth Story started panning out, and industry went into overdrive.

Companies started expanding and making capital expenditures even as the retail population, you and I, went out and bought cars, homes, second cars and second homes. Most of this was fuelled by bank loans, which, of course, came cheap.

And then, the cycle turned. Even as our wallets brimmed over, inflation shot up. So, the Reserve Bank of India began taking steps to bring down inflation and prevent the economy from overheating. Its answer: raising interest rates. And, that really is how the story of this decade has unfolded - from optimism to celebration to caution.

For us as consumers, this means a story of 'plenty to just enough'; for us as investors, this means turning our investments in debt products on their head. In the first few years of the decade, as interest rates softened (reduced), debt funds were spectacular investment areas, but other debt investments, such as bank fixed deposits, were duds. Fixed income debt fund managers in mutual fund houses were actively managing the kind of paper they bought and their funds were delivering an average of 10 per cent returns on a relatively low risk base.

As interest rates fell, they were holding high interest paying bonds, whose prices rose. So the funds made capital gains. And, in 2001, some of the gilt funds paid returns as high as 30 per cent.

Now, of course, inflation rates have risen, times have changed and, with it, avenues have been created for debt investments. If you are still invested in fixed-income, long-term debt funds, your money is probably earning nothing. In fact, your inflation-adjusted returns are likely to be negative. And suddenly, products like bank fixed deposits and fixed maturity plans have regained their sheen.

There is one issue that needs to be tackled before we go further. The stockmarket is at its volatile worst. It has come off its highest levels, but no one is considering that a blot on the long-term optimism of our economy. The question many are asking is, in this scenario, should you still invest in equities, or should you play it safe and invest in the high-return fixed deposits that sound unimaginably attractive at 10 per cent? This is the wrong question. It is certainly not an 'either-or' issue when it comes to equity and debt. In your portfolio, you need to allocate your assets to both.

The question that you should be asking is whether you should rebalance your debt. By that, we mean not only your your borrowings, or liabilities, but also investments, or assets. And the answer to that is a resounding yes.

Debt, in fact, is a double-edged sword. While times like these imply higher yielding debt instruments, they also mean paying a much higher rate of interest on the loans you have taken. Balancing the two is the key to managing your portfolio. Look at Rituraj Mehrotra. He took a hefty home loan about four months back at 9 per cent floating rate.

"The interest rate has been on the rise since then," he says. It went up from 9 to 9.5 to 10 to 10.5 and, then, to 11 per cent. "I found that the interest on home loans was 3 per cent in the US, 4-5 per cent in Singapore and 0.25 per cent in Japan. I thought the interest rate in India would also come down sometime soon. But, it has been the reverse here."

Mehrotra has also invested in fixed deposits, stocks and life insurance. He had invested in two FDs at 10 per cent return with ABN Amro Bank about eight months back. But, on 18 April, he broke the deposits to pre-pay a part of his home loan, which had swelled because of the hike in rates. So, while Mehrotra has a happy story to report as an investor, his calculations have gone awry as a consumer of debt.

Being a smart investor and borrower, he figured out that the post-tax, post-inflation return his 10 per cent FD would fetch would be around 1 per cent, while the effective cost of his housing loan after accounting for tax breaks would still be significantly higher at 7 per cent-plus.

In the following paras, we look at various kinds of debt assets and liabilities and calculate their returns and costs after accounting for taxes and inflation. Comparing them should make the task of rebalancing your debt a pretty easy one. Just remember, a penny saved is a penny earned. So, here are five strategies that should deliver the goods for you.

The strategy

Although rising interest rates have made most debt funds unattractive (interest rates and prices of debt securities move in opposite directions), you could still make money from two classes of debt funds: fixed maturity plans and liquid funds.

Fixed maturity plans. FMPs are closed-end debt funds that invest in securities that mature at or around the same time as the FMPs do. These plans warrant that you stay invested till maturity to negate the impact of interest rate volatility. Although MFs are not allowed to assure returns, most FMPs disclose the yield that you are most likely to get if you stay invested till maturity. The indicative yield currently in the market for a 1-year FMP is between 9.5 and 9.9 per cent.

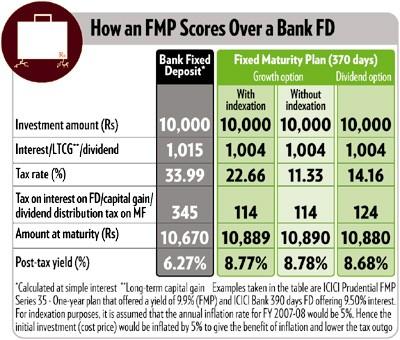

Says Ashish Nigam, fund manager, DBS Chola MF: "FMPs do not compromise on credit quality." While the tenures are comparable, FMPs are more tax-efficient than bank FDs if you are in the higher tax slabs (see How an FMP scores over a bank fixed deposit).

The returns of FMPs are more tax-efficient than those of bank FDs if you are in the 20.6 per cent, 30.9 and 33.99 per cent tax brackets. If you belong to the last one, Rs 10,000 invested in a 390-day bank FD that offers 9.5 per cent interest would leave you with Rs 10,670 after tax and your effective yield would drop to 6.27 per cent.

However, if you invest in an FMP that matures in just over a year (370 days) and yields 9.9 per cent, your returns after tax drop to only 8.78 per cent in the growth option. Since the FMP is more than a year old, you end up paying just 11.33 per cent (including surcharges and cess) as long-term capital gains tax. So opt for the growth option.

FMPs no longer offer double indexation benefits as the 31 March 2007 deadline for that is over, but it still pays to invest through them. Check with your agent about ongoing FMPs, their tenures and their indicative yields before choosing the best one.

Short-term FMPs. Short-term FMPs or Quarterly Interval Plans (that come with a maturity of 90 to 181 days) are short-term alternatives, if you are sure you won't need the cash before the FMPs mature.

As FMPs are not classified as liquid funds, a lower dividend distribution tax (DDT) of 14.163 per cent is levied on them. There is, of course, the catch that one needs to stay invested till maturity to get the indicated yield. Premature withdrawals impose a high exit load (usually 0.75 per cent) and you may end up earning much less than the indicated yield.

Liquid funds. Budget 2007 took away some sheen from liquid funds by increasing the DDT on them to 28.325 per cent (including surcharges), up from 14.025 per cent earlier. But if you are in the highest tax bracket, it still pays to park your cash here.

Bond and gilt funds. Avoid bond and gilt funds for now. Fund managers feel that interest rates would peak in May and June. If this happens, we could see interest rates stabilising a bit, or perhaps falling. That will be a good time to enter long-term bond funds. We will keep you posted.

The fixed income deposit strategy

TV advertisements and banners fluttering in your city would have you believe that FDs are the hottest instrument this summer. The return on bank FDs has gone up to 10 per cent, an unthinkable rate even a year ago. While bankers concede that these are high rates, they are not ruling out a further hike, even though it is expected to be marginal (an addition of 25 to 50 basis points).

Says Sumant Kathpalia, head (consumer banking), ABN Amro Bank: "The 10.25 per cent return on a FD is in response to the latest measures announced by the RBI, primarily the CRR and repo rate hikes of 30 March. We also expect liquidity in the market to be tighter with interest rates heading north. It looks like the rates would stay firm at current levels, or go up in the near future."

There have been many takers for these high-return fixed deposits. Says O.V. Bundellu, deputy managing director, IDBI Bank: "Special FD rates have seen a good response from investors. There has been an increase of 67 per cent in our total deposits since last year because of our special FD schemes offering 9.5 per cent interest. Senior citizens have also shown keen interest in these schemes."

All these instruments are for a fixed period and their rate of interest is fixed for the entire tenure at the time of investing. Though the hike in FD rates is for new investors, existing depositors can break their earlier investments and redirect them to these higher-rate products. Our analysis shows that even though fixed deposits are more attractive now than they were earlier, they may still not necessarily be the best place to park your money. You need to take real returns into account.

There are two major costs waiting to eat into your returns from these instruments. One is inflation and the other is tax. What you must determine is your actual rate of return, and this is usually very different from what is advertised in TV commercials, or those fluttering banners.

Check how much your investments really earned last year, or how much they will earn in the coming year. If you do not adjust the rate of return for inflation and taxes, you will not get the real rate of return.

The nominal interest rate gives you the growth rate of your money, while the real interest rate tells you how much your purchasing power has grown (See Real returns on fixed deposits).

The Real Returns on Fixed Deposits:|

100,000 |

9,000 |

109,000 |

2,781 |

106,219 |

100,908 |

0.9% |

|

Principal invested |

Interest earned at 9% |

Maturity amount on year-end |

Tax @ 30.9% on interest |

Post tax balance |

Post inflation at 5% |

Real return (%) |

For example, if you invest Rs 100,000 and it earns 9 per cent in one year, you end the year with Rs 109,000 at simple interest. In other words, your money has grown by Rs 9,000. However, if inflation is 5 per cent for the year, your Rs 109,000 is worth only Rs 1,04,000.

If the instrument is not tax-free in nature, the income earned is subject to tax as well. So, the other deduction you need to make to reach the real rate of return is for taxes. For the sake of simplicity, let us assume that you are paying 30.9 per cent tax. The tax paid would be Rs 2,781 of the Rs 9,000 you have earned. This will bring your real bank account down to Rs 1,06,219 from Rs 1,09,000.

If we apply the 5 per cent inflation to what you will actually get after the tax deduction, we will come up with the real purchasing power your investment returned. This figure is Rs 1,00,908 (95 per cent of Rs 1,06,219). The ugly bottomline is that after one year, after accounting for inflation and taxes, the purchasing power of your investment of Rs 100,000 has increased by only 0.9 per cent!

So, should you not invest in a 10-per cent fixed deposit?

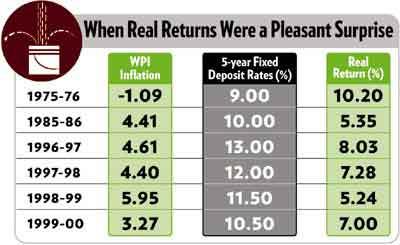

Well, the answer is you could, but keep your fingers crossed about what your real return would be. We dug up data for 37 years, from 1970 to 2007, compared interest rates and set them off against inflation to find real returns. This is what emerged: real returns on fixed deposits were under 5 per cent for most of these years. However, there were a number of windows where these pleasantly surprised investors.

For example, the years 1996 to 2000 were bumper years in terms of real returns. During three of these years, real returns exceeded 7 per cent. In 1996-97, it was a whopping 8.03 per cent. The highest real return, for those who are statistically inclined, was 10.2 per cent in 1975-76 (see When Real Returns Were a Pleasant Surprise).

What does this mean for your money now? Simply put, this: if inflation is contained to 5 per cent or less, and various factors, including the RBI's just-announced Monetary Policy for 2007-08, seem to suggest that this could well be the case, then it might make sense for you to lock in some of your money in these high-return FDs. The real returns figure could be pleasing in this year and the next. Moreover, bank deposits with a tenure below five years do not carry any tax benefit. But then, this equation is all about inflation.

The deposits-with-tax breaks strategy

These instruments are similar to the fixed income deposits discussed in the preceding section, but tax breaks on them make a difference to the real rate of return.

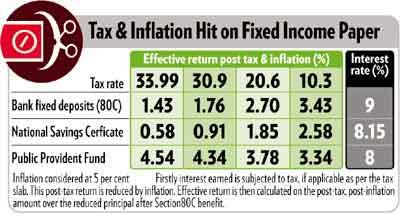

Public Provident Fund. Investment in PPF fetched a return of 8 per cent per annum last year. This figure, however, is not fixed, but decided by the government every year. In a scenario of increasing interest rates, it is unlikely to fall below that level in the near future. But there is a catch. The maximum amount you can put into a PPF account in a particular year is Rs 70,000. The 8 per cent interest earned is tax-free.

Assuming an inflation of 5 per cent, the post-inflation return is about 3 per cent. Now, if you are in the highest income slab of 33.99 per cent (including cess and surcharge), taking Section 80C benefits into account, your effective return will work out to 4.54 per cent [3/(100-33.99)x100]. This is by far the highest post-tax, post-inflation return you can get from any fixed income instrument.

Bank fixed deposits with Section 80C benefit. Bank deposits below five years do not give any tax benefit on the amount invested. The interest earned is also fully taxable. However, notified bank deposits of 5-year tenure carry tax benefit under Section 80C of the Income Tax Act. You can earn an interest of 9.0-9.5 per cent per annum on them. At an effective income tax rate of 33.99 per cent (including cess and surcharge), if the return earned is 9 per cent per annum and inflation is at 5 per cent, the effective post-tax, post-inflation return comes down to around 1.43 per cent.

National Savings Certificates. National Savings Certificates would lock in your investment for six years and yield a return of 8.15 per cent per annum. Under Section 80C of the Income Tax Act, the investment is deductible from taxable income to the extent of Rs 1 lakh, but its interest is fully taxable. Factoring in a 5 per cent rate of inflation, the effective post-tax, post-inflation return would work out to be about 0.58 per cent.

One must remember here that the maximum amount that is deductible from taxable income is Rs 100,000 for all these investments put together, plus other investments such as provident fund, that qualify for benefit under Section 80C. Beyond that, if you are in the highest tax slab, the post-inflation rate of return works out to 3 per cent for PPF, about 1 per cent for bank deposits, and 0.38 per cent for NSCs.

The home loan strategy

While it may be party time as far as your investments are concerned, it is payback time in the case of your loans. The rate hikes have arguably hit home loan seekers the hardest. Home buyers, who made their EMI calculation based on 8, and even 7 per cent interest rate, are now seeing the tenures on their loan as well as the EMI amounts increase geometrically.

Prepay the loan. The simple answer here is, if you have the funds, try and prepay as much of the loan as possible. Ideally, if you have maturing investments in NSC or excess cash in savings accounts or bank FDs without Section 80C benefits, these can be used to partly pay off the loan as the yields from these are lower than what you would pay as additional interest on the loan.

Refinancing the loan at this stage may be a bad idea. You would only end up paying more as the cost of refinancing. In fact, it could be a double whammy as you will first have to shell out prepayment charges for the existing loan and then current interest rates will apply for the refinanced loan.

Increase EMI, not tenure. Most banks have increased the tenure of the home loan after the interest rate hike. EMIs have been raised when the increase in tenure has stretched beyond the working life of the customer. "Although it will strain the financial budget of the family, it is a better for a person aged 40 to go for increase in the EMI rather than the tenure, once it has been extended to 25 years," says Harshvardhan Roongta, managing director, Apnaloan.com (for more strategies on home loans, see "Should You Prepay Your Home Loan?", 31 January 2007, and "Home Loans: Time to Take a Relook", 30 April 2007).

The car loan strategy

The auto loan story is a little different. If you have been planning to walk into a showroom and drive out in a new car, rising interest rates on car loans will hit you below the seat belt. Interest rates on auto loans have gone up by 1 per cent after the latest hardening by the RBI. So, if you are already saddled with a house loan, work out your finances well before going for a car as the total EMI outgo on a car loan would be higher than what it would have been if you had made the car purchase decision even a month back.

At the present rates, your total interest burden will constitute a substantial portion of the total cost. This is even more of a bad news than rising rates on home loans as unlike the house that is likely to appreciate in value, your car is a fast depreciating asset and loses a lot of its value as soon as it hits the road. Newspapers will tell you that car sales have plummeted as people have put off their decision to buy cars.

If, however, you really need a car, we suggest that you don't wait to make that purchase. Go for it now. It does not make sense to wait for a few months to see if interest rates fall. Even if they do by a percentage point in three months, your EMI per Rs 100,000 will go down by just Rs 45 for a 3-year loan. And there is always the possibility of the interest rate going up. Says Roongta: "A buying decision and a financing decision should always be separate. If you have decided to buy a car, you should go ahead." However, you could tweak your payment strategy.

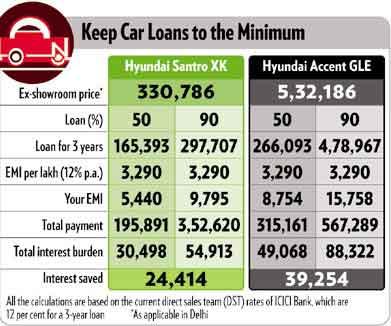

Larger down payment. To begin with, if you have the means, make a larger down payment and go for a smaller loan. This will bring down your EMI. For example, if you make a down payment of 50 per cent instead of 10 per cent for a 3-year loan for a Santro XK variant, you will pay around Rs 4,000 less as EMI and save an interest of Rs 24,414. For a car in the Rs 500,000-plus category, you will pay about Rs 7,000 less as EMI and save over Rs 39,254 in interest payment (see Keep Car Loans to the Minimum).

Shorter loan tenure. It is advisable to go for a 3-year loan than a 5-year loan. The magnitude of the interest burden in the former case will be lower. The case for taking a 3-year loan gets stronger as the price of the car and the loan amount increase.

Go for a less expensive model. Often, while buying a car, you end up stretching your limit. You might feel that you can afford to go for a costlier variant, but do you really need it? In a situation where interest rates might pinch, you should consider value for money. If your loan is for three years and covers 90 per cent of the cost of your car, then the EMI for a Rs 300,000-plus car works out to be about Rs 6,000 less than for a car that costs more than Rs 500,000. For a 5-year loan at 12.75 per cent, the difference in EMI works out to Rs 4,000.

Work on your deal. While negotiating, ditch that seven-CD changer and shop for a lower interest loan. Lower interest rates offered by dealers might be worth a look as, in their eagerness to reach their sales target, they are even willing to absorb some of the burden of making the car available to you at a lower cost.

Roongta suggests a way out: "Go for the lowest interest rates, and once you have zeroed in on the players who are offering them, see who is giving the largest discount. Always ask for the discount in cash, so that it is deducted from your loan amount. Factor in other costs like free insurance and accessories. Then go for the EMI which suits you the best."

Conclusion

Smart money managers strike a balance between churning the portfolio and keeping it stagnant. Outlook Money is in favour of long-term investment and against frequent churning of portfolios. But this is certainly one of the times when we would recommend that you rebalance your debt.

More from rediff